Crime in East Liberty on decline

In the 1990s, every crime in the city of Pittsburgh happened in East Liberty.

At least that’s what some people believed; and it was hard not to, especially when they would frequently hear television anchors read the grizzly details of violent crimes before signing off with, “Reporting live from East Liberty.”

But that was only because the live reports were coming from outside of the city’s Investigations Bureau and Zone 5 police station, which were both housed in the neighborhood.

“We had to call stations and tell them to not say, ‘Live from East Liberty,’ every time there was a rape in Pittsburgh,” says Lori Moran, board president of the East Liberty Chamber of Commerce.

The community’s attempts in ridding the news of the signoff represented the first of many battles to change the stigma of East Liberty; a stigma that has plagued community organizations and developers in their attempts to revitalize a once-booming area. Over the past decade, these organizations and developers, in collaboration with Zone 5 police, have worked tirelessly to change the perception, and the results have shown.

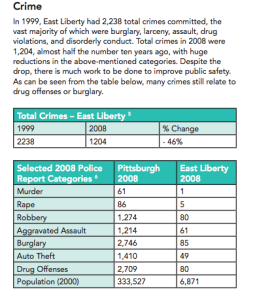

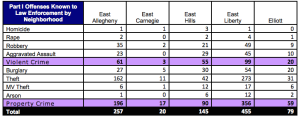

The perception of violence in East Liberty was at its worst in the late 1990s, even though the crime rate wasn’t alarming. In 1999, there were 911 Part I crimes – including robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, murder, rape and larceny – in East Liberty.

According to a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette story in May 2000, criminology experts at the time believed a neighborhood would be considered a problem area if more than 6 percent of the city’s total crime happened there. Crime in East Liberty amounted to approximately 4 percent.

But that didn’t mean there weren’t problems.

In the early 2000s, gang warfare was prominent in the neighborhood, according to former ELCOC director Paul Brecht.

“About ten years ago, you couldn’t wear gang colors or things of that nature in certain areas,” Brecht says. “East Liberty was safe, but only if you didn’t wear those colors.”

At the time, crime and gang activity were mostly concentrated in “hot spots,” most of which were abandoned properties or slumlord, according to a 2013 crime data analysis report.

Many of the crimes occurred in high-rise public housing units, which were built in the 1950s and 60s to lure residents away from the suburbs.

“The high-rises, they were a war zone,” Moran says. “When you have a 30-story apartment building of all low income people, after a while, if it’s not managed properly, it goes downhill.”

Down the hill the complexes went, and with them went the feeling of safety in East Liberty. The perception of danger in the slums masked the moderate crime rate, prompting the community to act.

The first action was taken by East Liberty Development Inc., the largest development corporation in the city. The ELDI purchased more than 200 “hot spot” units and assigned new property managers to regulate conduct.

Community organizations also moved forward with plans outlined in a 1999 restoration report called A Vision for East Liberty, which called for traffic studies, tree plantings, bicycle plans and land use plans. It also proposed that East Liberty phase out the aging storefronts and bring in new tenants to attract shoppers.

“As you put good tenants in, the hoodlums standing out front aren’t comfortable anymore,” Moran says. “When you fix it up, keep it clean, put a trash can out there, they don’t want to hang out in your alcove anymore. As we replace these nasty storefronts with newly decorated, well-lit storefronts, and we start filling them, the hoodlums go away.”

When retail giants Home Depot and Whole Foods opened along North Highland and Centre avenues in the early 2000s, they paved the way for other developers to confidently invest in East Liberty. The influx of commercial development positively impacted the crime rate, Zone 5 Commander Timothy O’Connor says.

“We’re trending down in crime in East Liberty,” O’Connor says, “and that decline is due to the effort to revitalize the neighborhood. You no longer have abandoned buildings, properties or an absence of vitality.”

Crime in East Liberty is steadily declining. From 1999 to 2008, there was a 46 percent drop in the total number of crimes committed in the neighborhood. Since 2010, total Part 1 offenses are down more than 17 percent, and the neighborhood actually has a lower number of crimes than Shadyside, which isn’t perceived as a high-crime area.

It’s still not entirely safe to walk outside in East Liberty at night, O’Connor says, especially after a disturbing murder on Chislett Street earlier this year. On Feb. 7, sisters Susan and Sarah Wolfe were found dead in their home. They were shot in the head.

But that shouldn’t stop residents from feeling “relatively safe” in their neighborhood.

“Even though crime is trending down, there’s always the potential,” O’Connor says. “We still do have some street crimes, particularly cars being broken into overnight and some people who are robbed on the street later in the evening. It would be best to walk in a group and use vehicle transportation if possible.”

Looking to the future, Moran says her organization is working with the community to develop a comprehensive system of surveillance cameras around crime-ridden areas in East Liberty. Also in the works is a strip of decorative lighting along Highland Avenue into Shadyside, funded by a $420,000 grant from the city.

The cameras and lights will symbolize yet another step forward in the war against a stigma of violence.

“It’s been a long road,” Moran says. “But it’s really coming along. We want this to be a community for everyone.”

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post